Vania Pigeonutt

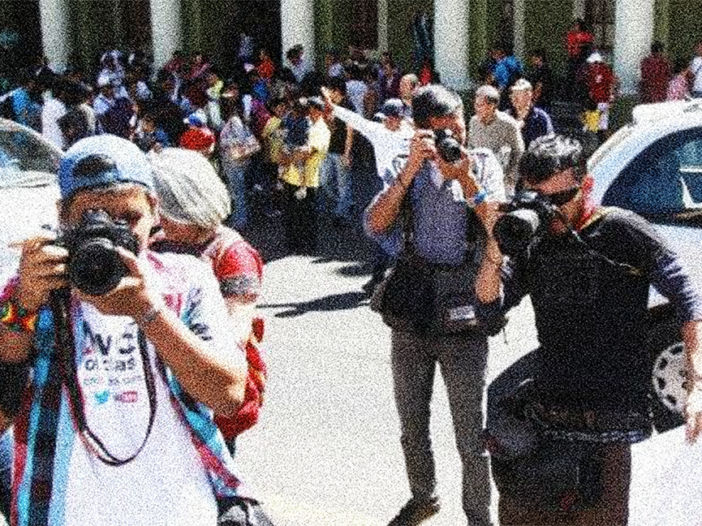

Félix Márquez, a photojournalist with 15 years of experience, has forged his career in local news programs that produce news in the midst of the continued violence that has taken over the state of Veracruz since 2000.

For more than two decades, this violence has stalked Veracruz reporters who carry out their work in the deadliest state for journalists. Article 19, an organization defending and promoting press freedom, has recorded the murder of at least 33 journalists between 2000 and 2023. The group also reports eight journalists missing in the same period.

The most recent Veracruz journalists murdered include José Luis Arenas Gamboa, Yessenia Mollinedo Falconi, Sheila Johana García Olivera and Pedro Pablo Kumul, all killed in 2022.

With this violence as backdrop, photojournalist Félix Márquez has developed a 15-year career working as a fixer for mostly foreign journalists; he’s also worked as a local field producer for film productions.

However, violence is not the only problem that Félix has had to deal with. He and his colleagues in other local media face the daily reality of low salaries.

This job insecurity made Félix to focus more on his fixer work in the last five years. But this work has not kept him from his personal projects such as “Vestigios”, a compilation of portraits of objects recovered by the families of seven Veracruz journalists murdered in the last decade.

Initially, Félix did not charge for his fixer services, but now he came up with fixed rates that vary depending on what the reporters who come to Veracruz are looking for. The topics that interest these journalists the most are insecurity, confrontations and the aftermaths of violence, but these subjects also present the highest risk because they involve entering dangerous areas.

Félix did his first jobs as a fixer during the governorship of Javier Duarte de Ochoa, between 2010 and 2016, a period that, according to data from Article 19, was the deadliest for the press in Veracruz: 18 journalists murdered and four more missing.

The list includes the murder of photojournalist Rubén Espinosa in Mexico City on July 31, 2015, just a few weeks after he fled the harassment he was experiencing in Veracruz.

Duarte de Ochoa is now serving a nine-year sentence for the crimes of using funds from illegal sources and criminal association, but not for any of the 18 reporters murdered during his six-year term. This is despite the fact that all the violence that Duarte exercised against the press during his governorship is documented.

According to an investigation by reporter Norma Trujillo, between 2010 and 2016, journalists from all over Veracruz filed 273 complaints for threats, theft, injuries, abuse of authority, disappearance of individuals, extortion, damages and defamation.

Félix remembers that during those same years he did not charge for his services because he believed that this would help him make connections and create a network that could help him if he needed to collaborate as a photographer with other media.

“I later realized that I was giving away my work, my knowledge, my experience. Besides, some media outlets have a budget for that,” he says.

Without asking for any compensation, Félix coordinated assignments in dangerous areas – where there were violent confrontations – or at events of then-governor Javier Duarte de Ochoa in which he was questioned about crimes against the press in Veracruz.

His first paid job was reporting on disappearances in the Santa Catalina hills, a subject he had already covered extensively as a photographer.

“I remember an assignment I did as a fixer for [a French newspaper] on various issues in the state: violence, migration, ungovernability and politics. That coverage was one of the most difficult because managing five issues is much more complicated. Fortunately, the work went well and there was very good pay,” he says.

Today, with more knowledge of the journalism industry, Félix earns between 100 and 400 dollars per day. He explains that his rate depends on what the reporters are looking for. However, his priority is to offer these correspondents his work as a photographer because he prefers to pursue his true passion behind the camera and not so much serve as a guide to other journalists.

This has worked for him, since some foreign media have taken him up on his proposal.

“I always offer packages when I am a fixer or producer. I offer the most basic thing which is to get contacts and be on the phone. For this, I try not to charge less than 150 per day. But many times because they are my contacts I cannot charge per day, so I connect with them and schedule their appointments for some money, depending on how many there are. If there are two or three, then I make it one day,” he says.

Felix’s work as a fixer consists of making contact with sources, booking interviews, taking journalists to the locations, establishing security protocols, driving, doing prior reporting or even reporting the stories.

Tamara Corro has worked 20 years as a reporter in one of the most violent regions of Veracruz: Coatzacoalcos. Despite her extensive experience, she has been a fixer on rare occasions.

Understanding that they are quite similar jobs, Tamara is certain that in Veracruz both fixers and journalists are in a state of complete helplessness. She is sure that those who perform this kind of work face insecurity, constantly take risks and do not receive credit or a fair pay for their work.

“One of the steps we take is that we do not want to be heroes. We go as far as it is safe for us. And yes, we like, as part of the job, to throw ourselves into everything, but it is necessary to have certain limits to avoid any problems,” she explains.

Tamara says that her bad experiences as a fixer have happened because she didn’t known how to charge fairly for high-risk assignments in which she has had to go into places where femicides, intentional homicides, disappearances, kidnappings and armed attacks happen frequently.

She says that one time reporters from a TV station in the United States that hired her to be their driver and schedule appointments, paid her less than $100 a day.

Another U.S. media outlet contacted her seeking her help in securing an interview with the local boss for a criminal organization, an almost suicidal assignment due to the risk involved in being the local contact in this type of reporting.

“I don’t really like getting into those topics. The further away I am the better for me, to keep my family safe,” she says.

She did not know that by working in a dangerous area she should charge more. It was until she participated in a Frontline Freelance Mexico workshop—part of the Fixing Journalism project—that she understood how to get paid better, what to do if the assignment is in a conflict region, or considering whether she runs greater risks as a woman.